Last week, the Home Office tried to deport Ifa Muaza, a 45-year-old Nigerian man who has been seeking asylum in the UK since July. James Bridle investigates the shadowy technological aspects of how Muaza was taken from London to the Mediterranean, to Malta and back again, and over multiple countries and jurisdictions.

Over the weekend, just before Amazon sucked all the air out of rational discourse with its absurd PR flim-flam about drone deliveries, a far more sinister aerial story was developing. On Friday, the British Home Office announced that it had deported Ifa Muaza aboard a private jet.

Ifa Muaza is a 45-year-old Nigerian man who has been seeking asylum in the UK since July. He claims he is under sentence of death from the Nigerian jihadist group Boko Haram, which he refused to join. His case has been supported by British politicians, peers, celebrities and human rights groups. Muaza has been on hunger strike at Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre since the beginning of August, and this week was reported to be close to death. Open Democracy reported on his case and the associated legal wrangling a few weeks ago, when he had been refusing food and water for 85 days, while the Guardian reported that he was expected to die in custody, despite a court ordering his release on mental and physical health grounds. According to Julian Huppert MP and Lord Roberts of Llandudno, by the beginning of last week he was “no longer able to see or stand”.

Despite his condition, Muaza was “fast-tracked” through immigration procedures and placed aboard a plane on Friday morning, on a stretcher, in an attempt to get him out of the country. The plan did not quite work out however: Nigeria refused to allow the plane to enter its airspace, and it diverted to Malta, where, according to the Guardian, “an angry dispute broke out with the authorities over the plane’s right to use its airstrip”. After flying for a reported twenty hours, the plane, with Muaza still on board, landed back at Luton in the UK, and the detainee was returned to Harmondsworth, the other side of London, hard up against Heathrow Airport and British Airways’ global headquarters.

The apparently unusual move of deporting detainees on private jets is not a first for the Home Office, which has previously used private aircraft to spirit contentious cases out of the country. The Home Secretary, Theresa May, who is currently looking for ways to strip Britons of their citizenship in contravention of British and international law, has used the tactic at least twice, including in the deportation of Abu Hamza, the fundamentalist cleric rendered to Jordan despite the clear threat of torture which should have stopped the process, again under both British and international law.

I wanted to know more about this journey. I find the shadowy technological aspects of these abominations against the person to be revealing of the underlying moral bankruptcy of the perpetrators. Technology is politics reified in electromechanical systems. When the government is deleting from the internet its own speeches promising greater transparency, consider this another kind of seeing through the cloud: an exercise in OSINT, using the tools of the network against its darkest masters.

According to media reports, Muaza’s plane left Britain at 8am on Friday 29 November, and returned, some twenty hours later, to Luton airport. I initially assumed it must have left from Luton as well, and examined the departure and arrivals at FlightRadar24 and FlightAware. However, these services do not cover most private flights. Plane-spotters, however, do. (I am indebted for this strategy to the work of Trevor Paglen, who has worked with enthusiasts worldwide in his research, most significantly tracing the CIA’s rendition programme in Torture Taxi.)

![Luton Spotters]()

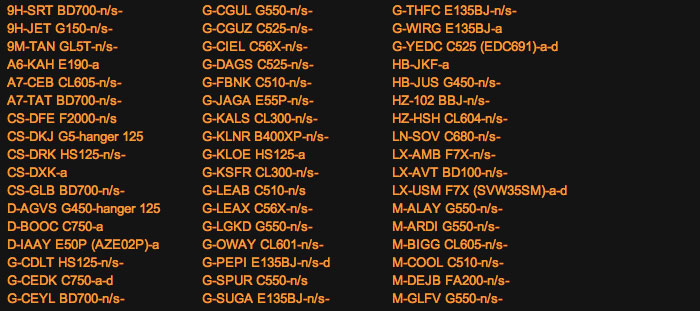

The spotter community is active online, and maintains sites such as Luton Movements, listing arrivals and departures from the airport. Comparing the logs for the relevant dates, I identified a couple of flights which roughly fit within the reported timings – but none of them matched exactly, and their flight paths, where visible, were indistinct, or unlikely.

Then I searched for similar communities in the aircraft’s other known location: Malta, the tiny island nation fifty miles south of Sicily, and two hundred north of Africa, in the middle of the Mediterranean. Malta has its own fascinating and hybrid history: both a Christian and a Muslim stronghold for centuries; part of the British Empire from 1814 until 1964, when it was a critical naval base; site of the first meeting between Gorbachev and Bush Sr in 1989, signalling the end of the Cold War. Of course, Malta has spotters too.

![Malta]()

There’s something obvious there: 29 November, an aircraft with the registration G-WIRG, an Embraer Legacy private jet, arriving and leaving on the same day.

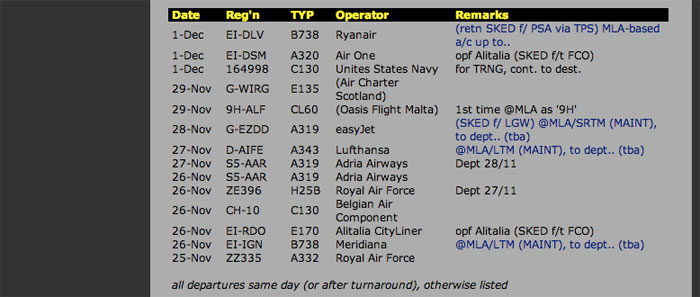

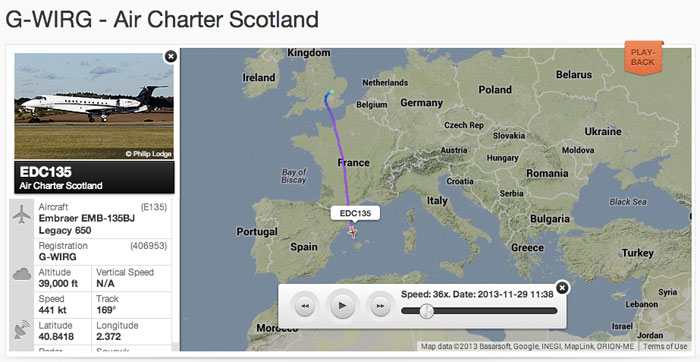

Back to FlightRadar24, and we can track G-WIRG’s journey. The Luton confusion is cleared up: on the friday morning it takes off at 08:26 (possibly 07:26 UK time), but from Stansted, another large, international airport north of London. (The logs show it was at Luton the day before though, on the 28th, departing at 18:00). It circles west around the city and heads south across France, passing over Barcelona at 11:23. Half an hour later, we lose the track – although this isn’t too unusual. FlightRadar24 uses tracking provided by ADS-B transponders aboard aircraft, with the data collected and passed on by a network of receivers on the ground. These receivers have a relatively short range, and are concentrated on the European mainland, which means coverage over the Mediterranean and Africa is poor.

We don’t know how far G-WIRG got before it was turned back by Nigerian air control, in the radar darkness – to European eyes – over Africa; what strange manoeuvres along designated air corridors between and across nations, climbing and banking to avoid thunderheads and moral accountability.

![G-WIRG Outbound]()

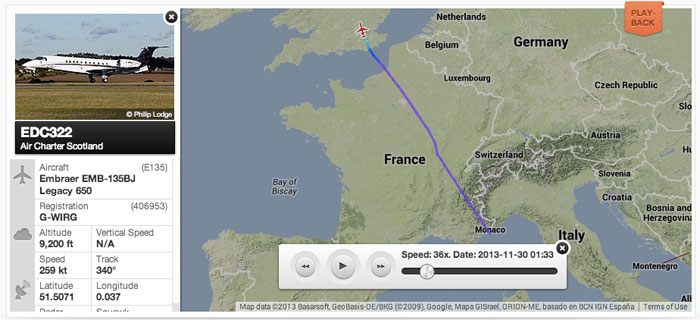

At some point later in the day, G-WIRG is spotted at Malta airport. And that night, the ADS-B beacon is picked up, approaching Nice on the southern France coast at 22:24 – an expected flight path northwards along the Italian coast from Malta. The jet passes over Paris at 36,000 feet a little after midnight (French time – an hour ahead of the UK), and the Luton spotters logs show it landing again at 00:05 UK time on Saturday the 30th, some sixteen hours after it left the country. With driving time from Heathrow to Luton/Stansted of around an hour, plus waiting time, Muaza, a man close to death from starvation and dehydration, clearly spent nearly a full day in transit, only to return to the same cage he started from.

![G-WIRG Inbound]()

The Embraer Legacy 650 is a twin-engined regional jet capable of carrying 13 passengers, “split in 3 areas: front club 4, middle club 4 and a separate area at the rear with a club 2 plus a 3 seat divan”. It is unknown how many officials accompanied Muaza on the trip. The media is reporting costs of £95,000 to £110,000 for the exercise. You can see photos of G-WIRG at airliners.net, photographed at Luton in October and November of 2013. It was only delivered to Air Charter Scotland, the operator, on 7 October– in these pictures, the registration is taped on – and it’s not listed on their website yet, but on 24 October they posted the following video to YouTube:

“You always wished to fly high. You always looked for freedom. You always dreamed of controlling time. Now you have it all.

“A legacy of freedom. This is your freedom to fly.”

- Embraer Legacy 650 G-WIRG operated by Air Charter Scotland Ltd promotional video

Air Charter Scotland is active on Twitter as well: they announced the arrival of G-WIRG in a series of tweets and photos from manufacture, to delivery, and into service. (Open Democracy, I later discovered, made the link to ACS some days ago.) ACS’ website is likewise full of exhortations to “Enjoy the peace and comfort of your own space… In today’s fast moving business world, time efficient travel is a key factor in staying ahead of the competition” – an invitation Theresa May clearly took up in her efforts to override the British justice system. ACS also operate Alan Sugar’s personal jet, with the predictable registration G-SUGA. Meanwhile, Embraer, the Brazilian manufacturer of G-WIRG, also produces the R-99, a military variant of the Legacy, used for remote sensing and AWACS missions. Brazil uses such jets to patrol the controversial Amazon Surveillance System, while the Greek Air Force deployed an R-99 to monitor the no-fly zone over Libya in 2011.

From London to the Mediterranean, to Malta and back again, over multiple countries and jurisdictions, through airspace and legal space. The contortions of G-WIRG’s flight path mirror the ethical labyrinth the British Government finds itself in when, against all better judgements, it insists on punishing individuals as an example to others, using every weasel justification in its well-funded legal war chest. Using a combination of dirty laws and private technologies to transform and transmit people from one jurisidiction, one legal condition and category, to another: this is the meaning of the verb “to render”.

At 10:08 on Saturday morning, G-WIRG departed Luton again, on some other mission, one of a network of obscure, advanced machines, looking for freedom, dreaming of controlling time. Ifa Musawa was back in Harmondsworth, still hungry, still looking for the same thing.

You can sign a petition in support of Ifa Musawa at epetitions, and consider donating to the Refugee Council, one of many British charities working in support of refugees and asylum seekers.

This article was originally published at BookTwo.org